As India gained Independence on August 15, 1947, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s speech “Tryst with Destiny” chimed on the radios at midnight while India was still struggling with a dire political and economic situation – the Partition that would culminate into the formation of two countries, India and Pakistan. But, the Independence Day we celebrate today, was earned after a collective hard work, one that cost millions of Indians their blood, sweat, and tears.

Let’s celebrate this day by commemorating the sacrifices of our freedom fighters, and remembering some of the major events that led to India gaining Independence.

Revolt of 1857

Also known as the ‘Sepoy Mutiny’, it continued for two years, 1857–59. It was also known as the First War of Independence as it was the first time that Indians presented a united front to fight back against the oppressive rule of the British. It began in Meerut with Indian troops (sepoys) in the service of the British East India Company and then, gradually spread to Delhi, Agra, Kanpur, and Lucknow.

The 1857 Revolt clamoured down the strong foundation of British Rule such that the East India Company’s rule was dissolved and its powers transferred to the British Crown in 1858.

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre

Owing to the new-found unity after Mahatma Gandhi’s return to India from his brief stint as a lawyer in Africa, Satyagraha became a common form of protest. Recognising the different ways in which the British power infiltrated the major institutions of India, Indians took to the streets to attack courts, schools and everything else that stood as a symbol of British oppression. As a result of this, in 1919, the British government had released an order banning public gatherings to punish civilians for their ‘disobedience’.

However, thousands of Indians gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar on April 13, 1919, to celebrate the festival of Baisakhi. Misconstruing this as a way of gathering to strategize against the British, General Dyer ordered the troops to open fire at the mass gathering. Although official records claim that 350 people died in it, Congress declared the actual figure to be as high as 1,000 people.

It was this event that opened doors to a higher degree of resistance through the Non-Cooperation Movement.

Non-Cooperation Movement

In 1920, as Mahatma Gandhi took charge of Congress, he propagated the idea of ‘non-cooperation’ – the act of refusing to engage in any activity that would indirectly strengthen the status of the British, to further make the British give in and grant Indians ‘Swaraj’ or self-government.

Boycotting British goods and supporting Swadeshi goods, picketing alcohol shops, resigning government titles, boycotting elections, and even refusing to pay taxes, were a part of the mass movement. However, Gandhi called off the movement in 1922 when a protest at the Chauri Chaura police station turned violent.

The Dandi March of 1930

The British had exercised a monopoly on the production of salt and its distribution for a very long time whereas salt was a basic commodity for all Indians- rich and poor. This caused severe economic distress to the masses.

Gandhi pledged to march from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi beach and make salt on his own, as a symbol of resistance against the draconian salt tax. Lakhs of people joined him in his journey which later became an emblem of non-violent protests.

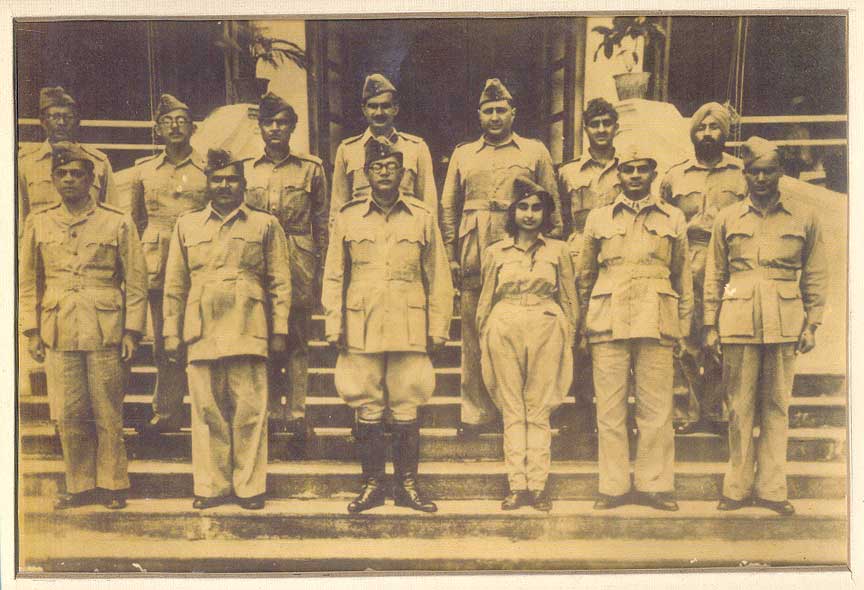

Creation of the Indian National Army

The Azad Hind Fauj or the Indian National Army (INA) was formed under the leadership of Subhash Chandra Bose during the Second World War. The army consisted of nearly 45,000 soldiers, most of whom were Indian prisoners of war. Bose also approached global leaders to render strength, vigour, and international validation to the Indian struggle for absolute freedom.

In 1943, he visited Japan to rebuild the INA. The same year he also formed a provisional government that had been recognised by the Axis Powers during the Second World War. Although his moves were opposed by the Congress and Mahatma Gandhi, he left no stone unturned to overthrow the British rule, even at the cost of the fight turning violent.

These events and many more stark instances of the deep-seated desire to live and breathe in a country that is sovereign from its very core led to the Parliament of the UK passing the Indian Independence Act. As per the Act, British India would be divided into India and Pakistan. The British Crown gave its assent to the Act on July 18, 1947, and it came into effect on August 14-15 in Pakistan and India respectively.